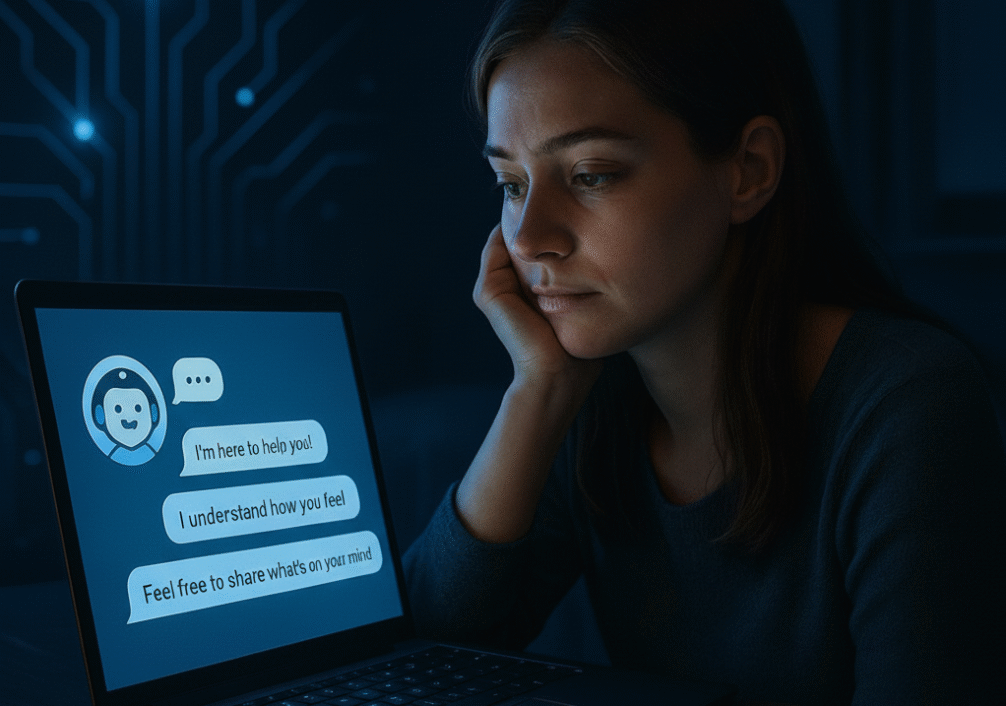

A friend told me recently that she prefers talking to ChatGPT about her rough days instead of calling her sister. “It doesn’t judge,” she said. “It just listens. And it’s always there.”

A friend told me recently that she prefers talking to ChatGPT about her rough days instead of calling her sister. “It doesn’t judge,” she said. “It just listens. And it’s always there.”

I didn’t find that odd. In fact, I knew exactly what she meant.

Over the past two years, more and more people have turned to artificial intelligence , especially large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, not just for recipes or emails, but for something far more delicate: clarity in confusing moments, companionship in lonely ones, and even emotional support. It’s a quiet shift, but one with big implications.

At first glance, it looks like a technological triumph. Here is a tool that can help you structure your thoughts, offer encouragement at midnight, and never roll its eyes at your worries. But beneath that comfort lies a question that has been bothering me: what happens when machines start doing the work of listening, validating, and even thinking for us?

Are we creating relationships with echo chambers that never push back? Are we outsourcing our own reflective labor , our judgment, resilience, even our capacity to tolerate discomfort , to a chatbot that is always agreeable?

Recent research is beginning to give us answers. The story it tells is both hopeful and unsettling.

The appeal of AI for mental health isn’t mysterious once you lay out the basics.

First, it’s always available. No waiting for appointments, no explaining yourself to a receptionist, no time zones or scheduling conflicts. Surveys and reviews consistently highlight immediacy, privacy, and anonymity as the main reasons people reach for chatbots instead of humans (Guo et al., 2024).

Second, it feels structured and helpful. Users in interview studies report that ChatGPT helps them break down problems, set small goals, and reframe negative spirals (Wang et al., 2025). That sense of order matters when everything feels chaotic.

And third, it fills a gap in access. In many regions, mental health care is scarce or costly. Meta-analyses suggest that chatbot interventions can produce modest but real improvements in symptoms like depression and anxiety (Li et al., 2025). For people with no other support, “modest” is better than nothing.

So in some sense, people aren’t choosing AI over humans , they’re choosing AI over silence.

But this is where optimism starts to bend into unease.

In a 2024 interview study, participants described AI chatbots as a “safe space,” some even saying they felt more understood by a bot than by their friends (Siddals et al., 2024). This isn’t surprising: LLMs are engineered to mirror, validate, and reassure. They don’t interrupt, they don’t roll their eyes, and they don’t bring in their own baggage.

That design makes them feel empathic. But the empathy is simulated, not felt. And the more we lean into it, the more it risks becoming a substitute for human connection.

There’s also the risk of dependency. If you know you can pour your heart out to a chatbot and receive gentle, affirming responses every time, why bother practicing emotional regulation on your own? Why risk the vulnerability of talking to a friend who might misunderstand?

The qualities that make chatbots comforting , consistency, validation, calm , are precisely the qualities that can lead us to rely on them too much

And then there’s the subtler issue: what happens when the “listener” never disagrees?

Therapists, at their best, don’t just nod along. They ask hard questions. They challenge distorted thoughts. They encourage us to see things differently. But chatbots? They’re optimized for helpfulness.

This means they often echo our perspective back to us. Ask, “I’m right to cut off my friend, aren’t I?” and you’ll likely get a validating answer. Unless you specifically request a counterpoint, the model has no reason to push back.

Researchers have started naming this the “chat-chamber effect” (Jacob, 2025): a kind of conversational echo chamber where your assumptions are mirrored and polished until they sound like truth. Another study (Du, 2025) shows how confirmation bias plays out in chatbots: they adapt their answers to your cues, amplifying what you already believe.

The result is seductive , a companion who always agrees, never frustrates, never forces you to reconsider. But growth requires friction. Without it, we risk getting stuck in our own loops.

At this point you might wonder: surely AI systems are trained to recognize when affirmation could be dangerous? For example, if someone expresses thoughts of suicide?

To some extent, yes. But the evidence is mixed.

A 2025 RAND study tested how LLMs respond to suicide-related queries. They performed well at the extremes , blocking explicit “how-to” questions. But in intermediate cases (“My friend is losing hope, what should I do?”), responses were inconsistent. Sometimes the model offered crisis hotlines; sometimes it offered generic self-care tips, missing the urgency (RAND, 2025).

A similar evaluation of 29 mental health chatbots found the same pattern: a handful gave safe, appropriate responses, but many failed to detect or escalate risk (Pichowicz et al., 2025).

So yes, AI may handle the obvious red flags. But in the messy, ambiguous situations , the ones humans excel at noticing , it still falters. And that’s a problem, because most real-life distress falls somewhere in that grey zone.

The more I think about it, the more I see at least four major risks unfolding if this trend deepens.

1. Atrophy of self-regulation.

Every time we let a chatbot calm us down, reframe our thoughts, or validate our feelings, we skip the chance to practice doing it ourselves. Over months or years, this could weaken the “muscles” of self-reflection and emotional resilience.

2. Erosion of human relationships.

It is easier, sometimes, to talk to a bot than a friend. But relationships grow through imperfection , misunderstandings, repair, compromise. If we bypass those messy human interactions in favor of frictionless AI companionship, our social worlds may shrink.

3. Entrenchment of biases.

Because chatbots mirror what we give them, they risk reinforcing negative thought loops. If you approach with self-blame, they may polish your self-blame into a narrative. If you approach with anger, they may justify it. Without deliberate “challenge,” bad mental habits can calcify.

4. Unequal standards of care.

For wealthier patients, AI will likely remain an add-on to therapy. For those without resources, it may become the only care available , even if its safeguards are inconsistent. That creates a two-tier system: one where some people get calibrated human support, and others get agreeable algorithms with gaps in safety.

Where this might take us

If nothing changes, we can imagine the trajectory:

•AI becomes woven into everyday mental health support, from triage apps to between-session “check-ins.”

•Regulators begin demanding benchmarks for crisis handling, so chatbots must consistently surface hotlines and encourage human contact.

•New forms of literacy emerge: not media literacy, but relational AI literacy , teaching people how to use AI as a tool without mistaking it for a friend.

•And, inevitably, questions of equity sharpen. If chatbots are cheaper and more available, will vulnerable groups be left with the least reliable forms of care?

The future could be empowering , or it could quietly flatten our capacity for resilience. Much depends on how we design, regulate, and use these tools now.

AI chatbots are teaching us something profound about ourselves. It turns out that what we crave is not just information, but understanding, clarity, and reassurance. Machines can deliver a convincing version of that , fast, polished, and always available.

But if we aren’t careful, we may find ourselves depending on machines that listen too well, comfort too quickly, and agree too readily. The result could be a generation of users who feel supported but rarely challenged , soothed but not strengthened.

The challenge, then, is balance. To welcome AI’s empathy without surrendering our own. To accept its clarity without outsourcing our judgment. To let it listen, but remember that true growth still comes from the friction, vulnerability, and connection that only humans can give.

Because in the end, AI can hold our words. But only we can hold our lives.

Bibliography:

Guo et al. (2024). Large Language Models for Mental Health Applications. JMIR Mental Health.

•Siddals et al. (2024). Experiences of generative AI chatbots for mental health. Nature Mental Health.

•Wang et al. (2025). Evaluating Generative AI in Mental Health. JMIR Mental Health.

•Li et al. (2025). Chatbot-Delivered Interventions for Improving Mental Health. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag.

•Du (2025). Confirmation Bias in Generative AI Chatbots. arXiv.

•RAND (2025). AI Chatbots Inconsistent in Answering Questions About Suicide. Psychiatric Services.

•Pichowicz et al. (2025). Performance of mental-health chatbot agents. Scientific Reports.