Making a case for a Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) Act for America

AUTHOR: Mitul Jhaveri

Published on October 3, 2025

The U.S. once led the world in building railroads, highways, and the internet. Today, it lags in the digital infrastructure that underpins identity, payments, and data. Public Digital systems should be as essential to daily life as roads and bridges, yet America’s digital foundation is fractured and incomplete.

The missing pieces in America’s Digital foundations

Digital public infrastructure (DPI) refers to a set of core and foundational digital systems like identity, payments, and data exchange that makes it easier for people, businesses, and governments to securely connect, transact, and access services.

America’s current digital landscape is a patchwork of systems across states, agencies and private companies and misses an interoperability layer. This means fragmented identity verification, uneven instant payment networks, and siloed data exchange rules and mechanisms. This fragmentation not only frustrates citizens but also costs taxpayers billions, leads to inefficiency and fraud.

Let us break down the state of these digital public infrastructure pillars now and then make a case for an integrated approach to a Act Digital Public Infrastructure in the U.S.

Identity: The U.S. has no universal digital identification system. Proving who you are online often relies on a jumble of methods like scanning driver’s licenses, giving your social security number, or one-off logins. Unlike many countries with national e-ID schemes, the U.S relies on the REAL ID law which sets higher standards for physical driver’s licenses, but it provides no digital ID or consent mechanism for online use. Only 13 states have rolled out some form of mobile driver’s license (mDL) or digital ID, and each implementation is largely unique.

Federal agencies have tried to streamline login with services like Login.gov, yet many agencies still contract separate solutions (Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, Okta, etc.), leading to duplication. The Government Accountability Office recently found that two dozen major agencies use a mix of at least five different identity-proofing providers. The result is an identity verification landscape that is inconsistent and costly, both for users and the government.

Payments: The U.S. lags in offering universal, real-time payments accessible to all. The U.S. payments landscape is highly fragmented, with multiple systems operated by different public and private entities, each governed by distinct rule sets. The Automated Clearing House (ACH) network is co-run by the Federal Reserve (FedACH) and The Clearing House (EPN), with rules set by Nacha; it processes batch credit and debit transfers, settling with delay. The Real-Time Payments (RTP) Network, launched by The Clearing House in 2017, provides instant, credit-push payments using a prefunded joint account model at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and is governed by rules set by its private bank owners.

In contrast, FedNow, launched by the Federal Reserve in 2023, offers instant settlement through banks’ Fed master accounts under public governance. Alongside these, card networks (Visa, Mastercard, Amex, Discover) operate as private, proprietary schemes, while peer-to-peer services such as Zelle, Venmo, and CashApp run closed-loop systems that ultimately rely on RTP for settlement.

Because these systems differ in ownership, governance, settlement models, and liability frameworks, they are not natively interoperable: a payment sent on RTP cannot be received on FedNow, and card or wallet systems do not seamlessly interact with ACH or instant rails. Unlike India’s UPI, which is a single shared platform with mandated interoperability across all banks and apps, the U.S. model reflects a patchwork of competing infrastructures, where interoperability is left to intermediaries or orchestration layers rather than built into the rails themselves.

The Federal Reserve’s new FedNow service (launched July 2023) finally gives the U.S. a public instant payment rail, but the adoption is voluntary and slow. FedNow started with only 35 participating banks; a year later about 820 institutions were live, still under 9% of the nation’s banks. It is a great start, indeed.

The real-time payments systems in India (UPI), Brazil (Pix) and the UK (Faster Payments) all process a considerably higher number of transactions. This indicates the extent to which these systems have become embedded in these countries.

This fragmented payment ecosystem became painfully apparent during COVID-19: some people waited weeks or months for stimulus and unemployment checks, while fraudsters exploited the delays. Only in 2025 did the Treasury Department finally announce it will stop issuing paper checks for most federal payments, to reduce delays, fraud, and theft.

Clearly, the U.S needs a more cohesive approach to instant, secure payments, from Government-to-Person (G2P) benefits to Person-to-Government (P2G) tax payments and everyday Person-to-Person (P2P) transactions.

Data Exchange: Americans routinely confront data silos and repetitive paperwork when interacting with different sectors and agencies. Health records are governed by health-specific standards (e.g. HIPAA and the new TEFCA framework for health information exchange), banking data by financial regulations (GLBA, emerging open banking rules), and tax or education records by their own rules.

There is no unified, citizen-centric protocol for individuals to consentingly share their data across sectors. For example, verifying your income for a mortgage, a student loan application, and a benefits program might require three separate data pulls from the IRS or employer, each with its own process. In healthcare, the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) is creating a nationwide data-sharing framework, but it’s voluntary and limited to medical providers. In finance, Europe’s PSD2 open banking rule (2018) forced banks to open consumer data via APIs, but the U.S. has only begun similar steps. The CFPB issued a proposed Personal Financial Data Rights rule aiming to mandate data portability by 2026. Overall, the data sharing rules remain sector-specific rather than citizen-centric, making it hard to “connect the dots” for services that span domains.

Data Protection: When it comes to data protection, the United States follows a fragmented, sectoral approach rather than a single, unified framework. Health information is covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA, 1996), financial data by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA, 1999), student records by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA, 1974), and children’s online data by the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA, 1998).

States have layered on their own rules, most prominently California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA, 2018) and California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA, 2020), which provide GDPR-like rights of access, deletion, and opt-out of data sale. At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fills gaps through its authority to regulate “unfair or deceptive practices” under Section 5 of the FTC Act, but there is no nationwide baseline for consent, portability, or deletion that applies across sectors.

An old illustration from 2021 by NYtimes shows the picture very well.

Efforts in Congress to pass a comprehensive statute i.e. American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) introduced in 2022 have stalled in committee, reflecting the political difficulty of balancing federalism, state innovation, and business interests.

The result is a system where Americans face both fragmented data exchange and fragmented data protection, undermining trust in digital public services and complicating any move toward a citizen-centric digital infrastructure.

The high cost of fragmentation

This patchwork system isn’t just inconvenient; it also bleeds billions of dollars. When agencies can’t reliably identify people, deliver payments quickly, or cross-check data, waste and fraud increase:

– Improper Payments: In FY2023 the federal government reported an estimated $236 billion in improper payments. That astronomical sum (almost a quarter-trillion dollars) stemmed from issues like payments to deceased or ineligible individuals and clerical errors. In fact, over 74% of the improper payments were overpayments (often to people who should not have received them). The largest drivers included Medicare/Medicaid billing mistakes and identity-verification failures in pandemic relief programs. For example, the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program alone saw an increase of $44 billion in erroneous payments, as identity thieves and imposter claims slipped through weak verification checks. While not all improper payments can be eliminated, a significant portion, GAO notes the biggest share results from documentation and eligibility verification weaknesses, not just intentional fraud could be reduced with better digital identity and data sharing systems.

– Identity Theft and Fraud: American consumers are suffering a wave of identity-related fraud. In 2023, the Federal Trade Commission received over 1 million reports of identity theft such as credit cards opened in your name, fraudsters hijacking unemployment benefits, and so on. Identity theft now accounts for about 17% of all consumer fraud reports. The surge during the pandemic (when government aid became a target) showed how criminals exploit weak ID verification. State unemployment systems, for instance, paid out a significant sum to fraudsters who used stolen identities. Strengthening the digital ID infrastructure in U.S could curb these losses by catching imposters before payments go out.

– Administrative Overhead: Fragmentation forces each agency and company to reinvent the wheel, at great expense. Consider identity proofing: federal agencies spent over $240 million from 2020–2023 on contracts for login and ID verification solutions, much of it to third-party vendors, despite overlapping functionality. States and private institutions likewise pour resources into redundant systems for onboarding and verifying users. Processing paper documents and manual checks adds further costs and an indirect cost of time and frustration for citizens. A GAO report noted that agencies have widely varying systems and that a coordinated digital identity approach could improve security and save money. In short, the lack of shared public digital infrastructure means higher costs and slower service across the board.

What would a Digital Public Infrastructure Act do?

It’s clear that the status quo isn’t working. The U.S. needs a Digital Public Infrastructure Act, a comprehensive federal law that would build the rails and rules for secure, efficient digital interactions nationwide. Just as past Congresses invested in highways and the internet itself, Congress today should invest in core digital systems to serve as public goods. A DPI Act could establish three pillars in particular:

1. Federated, Privacy-preserving Digital Identity: A secure digital ID that Americans can use (voluntarily) to prove who they are online, without creating a centralized “Big Brother” database. This would be a federated system, meaning you could choose from multiple trusted identity providers (for example, your state DMV, the Postal Service, or a certified private entity), all adhering to common standards. The system must follow the latest NIST digital identity guidelines for security and privacy (e.g. NIST SP 800-63) to ensure high Identity Assurance Levels.

Crucially, it should be privacy-preserving by design: using techniques like encrypted credentials and pairwise pseudonymous identifiers (so that each service you log into only sees a unique code, not your entire identity profile). A federated approach would leverage existing ID infrastructures (state IDs, passports, social security records) without replacing them, instead, it links and elevates them to a digital plane.

Under a DPI Act, an American citizen might verify their identity once through a trusted provider and then use that digital credential to access any federal or state service, open a bank account, or consent to a background check, with one login. This approach can dramatically reduce fraud (no more 5 different logins for 5 agencies) while protecting civil liberties by avoiding any single centralized ID database. The Act could establish a national trust framework (operating under agreed standards and audits) so that a digital ID issued in, say, Colorado is trusted by a bank in New York or a federal portal, just as state driver’s licenses are mutually recognized today. Done right, a digital ID saves time and protects privacy: imagine applying for benefits or a loan online by simply confirming a verified ID attribute (e.g. “I am Alice, over 18 and a U.S. citizen”) rather than scanning and emailing your driver’s license to unknown clerks.

2. Universal, real-time payments (G2P, P2G, P2P): The DPI Act should ensure that instant payment capability becomes as ubiquitous as email. This likely means leveraging FedNow, the Federal Reserve’s new instant payment rail, and expanding its use. For Government-to-Person payments, Congress could mandate that federal disbursements (tax refunds, Social Security, veterans’ benefits, emergency relief, etc.) use a real-time option by default, with an ACH or card fallback only if a recipient opts out.

No citizen should wait days or weeks for funds that could be sent in seconds. The same goes for Person-to-Government payments: taxes, fees, and fines should be payable instantly online, with immediate confirmation. This reduces float and uncertainty for both citizens and agencies. Finally, Person-to-Person: while the government doesn’t run private payment apps, a robust public instant payments infrastructure can connect banks of all sizes, enabling truly universal P2P transfers (so, for example, someone at Bank A can instantly pay someone at Credit Union B without needing both to join the same private app).

FedNow, as a public utility is an important player, but the Act could incentivize or require banks to join so no institution is left behind. The result would be a seamless national payments system where money moves as fast as email, enabling things like on-demand wage payments, rapid disaster aid, and easier commerce.

3. Cross-sector, Consent-based data exchange: The third pillar is perhaps the most forward-looking: creating standard protocols for data sharing that put individuals in control. Imagine a secure digital pipeline that lets you, the citizen, pull or push your personal data from one place to another with a click – for instance, authorizing the IRS to share your income info directly with a state college financial aid office, or allowing your bank to verify your identity by querying a DMV record (with your consent) instead of asking you to upload scans.

A DPI Act can establish an open-data exchange framework inspired by efforts like open banking and TEFCA, but broader. This framework would include technical standards (APIs, encryption, logging of data requests) and legal rules (what consents are needed, liability for misuse, etc.) to enable “tell us once” convenience for the public. Importantly, it must be consent-based: your data doesn’t move unless you approve and authorize it.

It can let you carry digital attestations i.e. driver’s license, vaccination, veteran status, etc. on an e-wallet and share just the necessary bits with whoever needs to know. Some building blocks already exist: the federal ONC is working on health data interoperability through TEFCA (so hospitals can query each other’s records), and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has begun rulemaking to give bank customers the right to share their financial data with third-party apps.

A DPI Act could unify these efforts under one umbrella, extend them to other domains, and fill in the gaps (for instance, enabling portable eligibility, if you qualify for one program, easily prove it for another). It could establish a governance entity or standards board to oversee the trust frameworks needed. Crucially, this must be accompanied by strong privacy and security measures like audit trails, encryption, and an emphasis that individuals can see and control who accesses their data (akin to how the EU wallet provides a dashboard for users to review and revoke data sharing)

The Digital Public Infrastructure Act would not necessarily build each piece from scratch but set national standards and provide funding to knit them together. It could, for example, direct NIST and a multi-agency task force to implement a federated ID by a certain date (building on Login.gov’s lessons), require the Treasury and Federal Reserve to ensure every American has a route to instant payments across platforms (leveraging FedNow), and authorize pilot programs for cross-sector data exchange in key areas like social services.

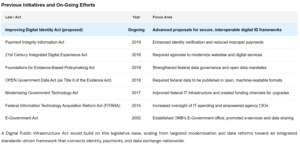

Precedent for such an approach already exists in bipartisan efforts:

A Digital Public Infrastructure Act would build on this legislative base, scaling from targeted modernization and data reforms toward an integrated, standards-driven framework that connects identity, payments, and data exchange nationwide.

Navigating roadblocks: federalism, privacy, and tech contractors

Enacting a U.S. Digital Public Infrastructure Act will face several real challenges. It’s important to acknowledge these roadblocks and consider strategies to overcome them:

• Federalism and Decentralized authority: Unlike many countries where a central government can launch a national ID or payments platform by decree, the U.S. must coordinate federal, state, and local authorities. Identity in the U.S. is traditionally a state domain (driver’s licenses, birth certificates), while federal agencies also issue identifiers (Social Security numbers, passports). A DPI solution must respect these layers. States may fear a federal takeover of their DMV role, and agencies might guard their IT turf. Solution: design the system as a federation of trust. The Act could explicitly empower states by providing grants for states to upgrade to digital driver’s licenses (the Improving Digital Identity Act proposed in 2022 did exactly this, offering grants for state DMV mobile IDs). It could also create a governance council with state CIOs and federal officials to jointly set standards.

Civil liberties and Privacy concerns: Any mention of a “digital ID” in America raises eyebrows about Big Brother. Civil liberties advocates will rightly question how to prevent government overreach or mass surveillance. The Act should incorporate privacy by design provisions e.g., require minimal data collection, mandate independent audits for security, and give users legal rights over their data. One promising approach is using decentralized identity technologies, where your personal data (like credentials) stay mostly on your device under your control, and only verification proofs are shared. Also, the law can explicitly forbid certain uses, for instance, prohibit law enforcement from fishing through the digital ID system without a warrant, or forbid using the digital ID for profiling citizens. Including groups like the ACLU and EFF in the drafting process could help address concerns early. It’s worth noting that privacy and security can actually be enhanced by a good digital ID: today, Americans hand over copious personal details to random companies for ID checks (e.g. scan of your driver’s license to rent an apartment, which might sit in a landlord’s email forever).

A federated ID could reduce exposure by only transmitting a yes/no verification or a single attribute, rather than a photocopy of your entire ID. Conveying that narrative, that this can protect people from identity theft and data breaches, will be key to overcoming knee-jerk opposition. Still, robust safeguards and perhaps a pilot phase to prove the concept will be needed to convince skeptics that a U.S. digital identity won’t become a surveillance tool.

Incumbent resistance (Big-tech and contractors): There are vested interests in the current disjointed system. Large federal IT contractors and identity verification vendors profit from selling agencies one-off solutions; big tech companies dominate payments and data silos in the status quo. A unified public infrastructure could be seen as competition or a threat to some business models. For example, if a free government-backed digital ID becomes widely accepted, companies like credit bureaus (which sell ID verification services) or ID.me might lose market share. If open-data sharing is mandated, banks that monetize data might push back. Solution is to engage industry in crafting the solutions so they can find new opportunities within the ecosystem. Many banks, for instance, actually support digital ID because it could cut fraud costs for them. The banking industry has been calling for better ID verification to fight account takeover and synthetic identities. In fact, a coalition of financial institutions endorsed the earlier Improving Digital Identity legislation.

Similarly, fintech companies often favor open data (it gives them more customers). The Act can create a public-private task force (as earlier bills proposed) to hash out implementation. For government contractors, the reality is that building DPI will still require significant IT work, just more standardized. Contractors who adapt can win contracts to build the new infrastructure.

• Political will and public perception: In today’s polarized environment, getting bipartisan support is tricky. Fortunately, DPI can be a bipartisan win if framed correctly.

For conservatives and fiscal hawks: emphasize the anti-fraud, waste-cutting angle. Stopping improper payments (recall that $236B figure!) and preventing identity theft aligns with the goal of efficient government. It’s essentially plugging leaky buckets, something everyone can get behind.

For liberals and tech-progressives: emphasize equity and empowerment. How digital infrastructure can help the unbanked access financial services, ensure eligible people aren’t left out of benefits, and give individuals control of their own data (a pro-consumer, anti-monopoly stance). Indeed, digital public goods are often framed as a way to ensure big tech doesn’t exclusively control our digital lives.

The key will be avoiding hot button mis-framings: this is not a surveillance program, not a national social credit system, etc. It’s an upgrade to basic government digital infrastructure. One strategy is to start with pilot programs and voluntary adoption to build trust. For example, the Act could fund a pilot in a few states to link a state’s digital driver’s license with federal Login.gov accounts, showing a working federated ID in action. Or pilot using FedNow for a chunk of tax refunds in one region. Early successes will create momentum and help refine the approach. Champions in the Congress will need to communicate that this is infrastructure in the truest sense: just as U.S. needed electrification and interstate highways, it now needs the digital equivalent to keep America competitive and secure.

By enacting a DPI Act, Congress can ensure that when Americans interact with their government or economy in the digital realm, it is as smooth and reliable as driving on the interstate or flipping on the light switch.

Originally published by Mitul Jhaveri on his Substack. Republished with due acknowledgment of the author and source.

Author

Mitul Jhaveri

Mitul Jhaveri is a Graduate Research Assistant at the Block Center for Technology & Society at Carnegie Mellon University, where he works at the intersection of artificial intelligence, energy, and public policy. His research focuses on how governments can collect better data and make more informed decisions on emerging technology issues.In addition, he is engaged as a Short-Term Consultant with the World Bank Group’s GovTech unit, contributing to digital transformation and data governance initiatives aimed at strengthening core government systems.He specializes in digital government reforms, leveraging data for policy decision-making, and enhancing public service delivery through technology.

Making a case for a Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) Act for America

Published on October 3, 2025

The U.S. once led the world in building railroads, highways, and the internet. Today, it lags in the digital infrastructure that underpins identity, payments, and data. Public Digital systems should be as essential to daily life as roads and bridges, yet America’s digital foundation is fractured and incomplete.

The missing pieces in America’s Digital foundations

Digital public infrastructure (DPI) refers to a set of core and foundational digital systems like identity, payments, and data exchange that makes it easier for people, businesses, and governments to securely connect, transact, and access services.

America’s current digital landscape is a patchwork of systems across states, agencies and private companies and misses an interoperability layer. This means fragmented identity verification, uneven instant payment networks, and siloed data exchange rules and mechanisms. This fragmentation not only frustrates citizens but also costs taxpayers billions, leads to inefficiency and fraud.

Let us break down the state of these digital public infrastructure pillars now and then make a case for an integrated approach to a Act Digital Public Infrastructure in the U.S.

Identity: The U.S. has no universal digital identification system. Proving who you are online often relies on a jumble of methods like scanning driver’s licenses, giving your social security number, or one-off logins. Unlike many countries with national e-ID schemes, the U.S relies on the REAL ID law which sets higher standards for physical driver’s licenses, but it provides no digital ID or consent mechanism for online use. Only 13 states have rolled out some form of mobile driver’s license (mDL) or digital ID, and each implementation is largely unique.

Federal agencies have tried to streamline login with services like Login.gov, yet many agencies still contract separate solutions (Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, Okta, etc.), leading to duplication. The Government Accountability Office recently found that two dozen major agencies use a mix of at least five different identity-proofing providers. The result is an identity verification landscape that is inconsistent and costly, both for users and the government.

Payments: The U.S. lags in offering universal, real-time payments accessible to all. The U.S. payments landscape is highly fragmented, with multiple systems operated by different public and private entities, each governed by distinct rule sets. The Automated Clearing House (ACH) network is co-run by the Federal Reserve (FedACH) and The Clearing House (EPN), with rules set by Nacha; it processes batch credit and debit transfers, settling with delay. The Real-Time Payments (RTP) Network, launched by The Clearing House in 2017, provides instant, credit-push payments using a prefunded joint account model at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and is governed by rules set by its private bank owners.

In contrast, FedNow, launched by the Federal Reserve in 2023, offers instant settlement through banks’ Fed master accounts under public governance. Alongside these, card networks (Visa, Mastercard, Amex, Discover) operate as private, proprietary schemes, while peer-to-peer services such as Zelle, Venmo, and CashApp run closed-loop systems that ultimately rely on RTP for settlement.

Because these systems differ in ownership, governance, settlement models, and liability frameworks, they are not natively interoperable: a payment sent on RTP cannot be received on FedNow, and card or wallet systems do not seamlessly interact with ACH or instant rails. Unlike India’s UPI, which is a single shared platform with mandated interoperability across all banks and apps, the U.S. model reflects a patchwork of competing infrastructures, where interoperability is left to intermediaries or orchestration layers rather than built into the rails themselves.

The Federal Reserve’s new FedNow service (launched July 2023) finally gives the U.S. a public instant payment rail, but the adoption is voluntary and slow. FedNow started with only 35 participating banks; a year later about 820 institutions were live, still under 9% of the nation’s banks. It is a great start, indeed.

The real-time payments systems in India (UPI), Brazil (Pix) and the UK (Faster Payments) all process a considerably higher number of transactions. This indicates the extent to which these systems have become embedded in these countries.

This fragmented payment ecosystem became painfully apparent during COVID-19: some people waited weeks or months for stimulus and unemployment checks, while fraudsters exploited the delays. Only in 2025 did the Treasury Department finally announce it will stop issuing paper checks for most federal payments, to reduce delays, fraud, and theft.

Clearly, the U.S needs a more cohesive approach to instant, secure payments, from Government-to-Person (G2P) benefits to Person-to-Government (P2G) tax payments and everyday Person-to-Person (P2P) transactions.

Data Exchange: Americans routinely confront data silos and repetitive paperwork when interacting with different sectors and agencies. Health records are governed by health-specific standards (e.g. HIPAA and the new TEFCA framework for health information exchange), banking data by financial regulations (GLBA, emerging open banking rules), and tax or education records by their own rules.

There is no unified, citizen-centric protocol for individuals to consentingly share their data across sectors. For example, verifying your income for a mortgage, a student loan application, and a benefits program might require three separate data pulls from the IRS or employer, each with its own process. In healthcare, the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) is creating a nationwide data-sharing framework, but it’s voluntary and limited to medical providers. In finance, Europe’s PSD2 open banking rule (2018) forced banks to open consumer data via APIs, but the U.S. has only begun similar steps. The CFPB issued a proposed Personal Financial Data Rights rule aiming to mandate data portability by 2026. Overall, the data sharing rules remain sector-specific rather than citizen-centric, making it hard to “connect the dots” for services that span domains.

Data Protection: When it comes to data protection, the United States follows a fragmented, sectoral approach rather than a single, unified framework. Health information is covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA, 1996), financial data by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA, 1999), student records by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA, 1974), and children’s online data by the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA, 1998).

States have layered on their own rules, most prominently California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA, 2018) and California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA, 2020), which provide GDPR-like rights of access, deletion, and opt-out of data sale. At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fills gaps through its authority to regulate “unfair or deceptive practices” under Section 5 of the FTC Act, but there is no nationwide baseline for consent, portability, or deletion that applies across sectors.

An old illustration from 2021 by NYtimes shows the picture very well.

Efforts in Congress to pass a comprehensive statute i.e. American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) introduced in 2022 have stalled in committee, reflecting the political difficulty of balancing federalism, state innovation, and business interests.

The result is a system where Americans face both fragmented data exchange and fragmented data protection, undermining trust in digital public services and complicating any move toward a citizen-centric digital infrastructure.

The high cost of fragmentation

This patchwork system isn’t just inconvenient; it also bleeds billions of dollars. When agencies can’t reliably identify people, deliver payments quickly, or cross-check data, waste and fraud increase:

– Improper Payments: In FY2023 the federal government reported an estimated $236 billion in improper payments. That astronomical sum (almost a quarter-trillion dollars) stemmed from issues like payments to deceased or ineligible individuals and clerical errors. In fact, over 74% of the improper payments were overpayments (often to people who should not have received them). The largest drivers included Medicare/Medicaid billing mistakes and identity-verification failures in pandemic relief programs. For example, the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program alone saw an increase of $44 billion in erroneous payments, as identity thieves and imposter claims slipped through weak verification checks. While not all improper payments can be eliminated, a significant portion, GAO notes the biggest share results from documentation and eligibility verification weaknesses, not just intentional fraud could be reduced with better digital identity and data sharing systems.

– Identity Theft and Fraud: American consumers are suffering a wave of identity-related fraud. In 2023, the Federal Trade Commission received over 1 million reports of identity theft such as credit cards opened in your name, fraudsters hijacking unemployment benefits, and so on. Identity theft now accounts for about 17% of all consumer fraud reports. The surge during the pandemic (when government aid became a target) showed how criminals exploit weak ID verification. State unemployment systems, for instance, paid out a significant sum to fraudsters who used stolen identities. Strengthening the digital ID infrastructure in U.S could curb these losses by catching imposters before payments go out.

– Administrative Overhead: Fragmentation forces each agency and company to reinvent the wheel, at great expense. Consider identity proofing: federal agencies spent over $240 million from 2020–2023 on contracts for login and ID verification solutions, much of it to third-party vendors, despite overlapping functionality. States and private institutions likewise pour resources into redundant systems for onboarding and verifying users. Processing paper documents and manual checks adds further costs and an indirect cost of time and frustration for citizens. A GAO report noted that agencies have widely varying systems and that a coordinated digital identity approach could improve security and save money. In short, the lack of shared public digital infrastructure means higher costs and slower service across the board.

What would a Digital Public Infrastructure Act do?

It’s clear that the status quo isn’t working. The U.S. needs a Digital Public Infrastructure Act, a comprehensive federal law that would build the rails and rules for secure, efficient digital interactions nationwide. Just as past Congresses invested in highways and the internet itself, Congress today should invest in core digital systems to serve as public goods. A DPI Act could establish three pillars in particular:

1. Federated, Privacy-preserving Digital Identity: A secure digital ID that Americans can use (voluntarily) to prove who they are online, without creating a centralized “Big Brother” database. This would be a federated system, meaning you could choose from multiple trusted identity providers (for example, your state DMV, the Postal Service, or a certified private entity), all adhering to common standards. The system must follow the latest NIST digital identity guidelines for security and privacy (e.g. NIST SP 800-63) to ensure high Identity Assurance Levels.

Crucially, it should be privacy-preserving by design: using techniques like encrypted credentials and pairwise pseudonymous identifiers (so that each service you log into only sees a unique code, not your entire identity profile). A federated approach would leverage existing ID infrastructures (state IDs, passports, social security records) without replacing them, instead, it links and elevates them to a digital plane.

Under a DPI Act, an American citizen might verify their identity once through a trusted provider and then use that digital credential to access any federal or state service, open a bank account, or consent to a background check, with one login. This approach can dramatically reduce fraud (no more 5 different logins for 5 agencies) while protecting civil liberties by avoiding any single centralized ID database. The Act could establish a national trust framework (operating under agreed standards and audits) so that a digital ID issued in, say, Colorado is trusted by a bank in New York or a federal portal, just as state driver’s licenses are mutually recognized today. Done right, a digital ID saves time and protects privacy: imagine applying for benefits or a loan online by simply confirming a verified ID attribute (e.g. “I am Alice, over 18 and a U.S. citizen”) rather than scanning and emailing your driver’s license to unknown clerks.

2. Universal, real-time payments (G2P, P2G, P2P): The DPI Act should ensure that instant payment capability becomes as ubiquitous as email. This likely means leveraging FedNow, the Federal Reserve’s new instant payment rail, and expanding its use. For Government-to-Person payments, Congress could mandate that federal disbursements (tax refunds, Social Security, veterans’ benefits, emergency relief, etc.) use a real-time option by default, with an ACH or card fallback only if a recipient opts out.

No citizen should wait days or weeks for funds that could be sent in seconds. The same goes for Person-to-Government payments: taxes, fees, and fines should be payable instantly online, with immediate confirmation. This reduces float and uncertainty for both citizens and agencies. Finally, Person-to-Person: while the government doesn’t run private payment apps, a robust public instant payments infrastructure can connect banks of all sizes, enabling truly universal P2P transfers (so, for example, someone at Bank A can instantly pay someone at Credit Union B without needing both to join the same private app).

FedNow, as a public utility is an important player, but the Act could incentivize or require banks to join so no institution is left behind. The result would be a seamless national payments system where money moves as fast as email, enabling things like on-demand wage payments, rapid disaster aid, and easier commerce.

3. Cross-sector, Consent-based data exchange: The third pillar is perhaps the most forward-looking: creating standard protocols for data sharing that put individuals in control. Imagine a secure digital pipeline that lets you, the citizen, pull or push your personal data from one place to another with a click – for instance, authorizing the IRS to share your income info directly with a state college financial aid office, or allowing your bank to verify your identity by querying a DMV record (with your consent) instead of asking you to upload scans.

A DPI Act can establish an open-data exchange framework inspired by efforts like open banking and TEFCA, but broader. This framework would include technical standards (APIs, encryption, logging of data requests) and legal rules (what consents are needed, liability for misuse, etc.) to enable “tell us once” convenience for the public. Importantly, it must be consent-based: your data doesn’t move unless you approve and authorize it.

It can let you carry digital attestations i.e. driver’s license, vaccination, veteran status, etc. on an e-wallet and share just the necessary bits with whoever needs to know. Some building blocks already exist: the federal ONC is working on health data interoperability through TEFCA (so hospitals can query each other’s records), and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has begun rulemaking to give bank customers the right to share their financial data with third-party apps.

A DPI Act could unify these efforts under one umbrella, extend them to other domains, and fill in the gaps (for instance, enabling portable eligibility, if you qualify for one program, easily prove it for another). It could establish a governance entity or standards board to oversee the trust frameworks needed. Crucially, this must be accompanied by strong privacy and security measures like audit trails, encryption, and an emphasis that individuals can see and control who accesses their data (akin to how the EU wallet provides a dashboard for users to review and revoke data sharing)

The Digital Public Infrastructure Act would not necessarily build each piece from scratch but set national standards and provide funding to knit them together. It could, for example, direct NIST and a multi-agency task force to implement a federated ID by a certain date (building on Login.gov’s lessons), require the Treasury and Federal Reserve to ensure every American has a route to instant payments across platforms (leveraging FedNow), and authorize pilot programs for cross-sector data exchange in key areas like social services.

Precedent for such an approach already exists in bipartisan efforts:

A Digital Public Infrastructure Act would build on this legislative base, scaling from targeted modernization and data reforms toward an integrated, standards-driven framework that connects identity, payments, and data exchange nationwide.

Navigating roadblocks: federalism, privacy, and tech contractors

Enacting a U.S. Digital Public Infrastructure Act will face several real challenges. It’s important to acknowledge these roadblocks and consider strategies to overcome them:

• Federalism and Decentralized authority: Unlike many countries where a central government can launch a national ID or payments platform by decree, the U.S. must coordinate federal, state, and local authorities. Identity in the U.S. is traditionally a state domain (driver’s licenses, birth certificates), while federal agencies also issue identifiers (Social Security numbers, passports). A DPI solution must respect these layers. States may fear a federal takeover of their DMV role, and agencies might guard their IT turf. Solution: design the system as a federation of trust. The Act could explicitly empower states by providing grants for states to upgrade to digital driver’s licenses (the Improving Digital Identity Act proposed in 2022 did exactly this, offering grants for state DMV mobile IDs). It could also create a governance council with state CIOs and federal officials to jointly set standards.

Civil liberties and Privacy concerns: Any mention of a “digital ID” in America raises eyebrows about Big Brother. Civil liberties advocates will rightly question how to prevent government overreach or mass surveillance. The Act should incorporate privacy by design provisions e.g., require minimal data collection, mandate independent audits for security, and give users legal rights over their data. One promising approach is using decentralized identity technologies, where your personal data (like credentials) stay mostly on your device under your control, and only verification proofs are shared. Also, the law can explicitly forbid certain uses, for instance, prohibit law enforcement from fishing through the digital ID system without a warrant, or forbid using the digital ID for profiling citizens. Including groups like the ACLU and EFF in the drafting process could help address concerns early. It’s worth noting that privacy and security can actually be enhanced by a good digital ID: today, Americans hand over copious personal details to random companies for ID checks (e.g. scan of your driver’s license to rent an apartment, which might sit in a landlord’s email forever).

A federated ID could reduce exposure by only transmitting a yes/no verification or a single attribute, rather than a photocopy of your entire ID. Conveying that narrative, that this can protect people from identity theft and data breaches, will be key to overcoming knee-jerk opposition. Still, robust safeguards and perhaps a pilot phase to prove the concept will be needed to convince skeptics that a U.S. digital identity won’t become a surveillance tool.

Incumbent resistance (Big-tech and contractors): There are vested interests in the current disjointed system. Large federal IT contractors and identity verification vendors profit from selling agencies one-off solutions; big tech companies dominate payments and data silos in the status quo. A unified public infrastructure could be seen as competition or a threat to some business models. For example, if a free government-backed digital ID becomes widely accepted, companies like credit bureaus (which sell ID verification services) or ID.me might lose market share. If open-data sharing is mandated, banks that monetize data might push back. Solution is to engage industry in crafting the solutions so they can find new opportunities within the ecosystem. Many banks, for instance, actually support digital ID because it could cut fraud costs for them. The banking industry has been calling for better ID verification to fight account takeover and synthetic identities. In fact, a coalition of financial institutions endorsed the earlier Improving Digital Identity legislation.

Similarly, fintech companies often favor open data (it gives them more customers). The Act can create a public-private task force (as earlier bills proposed) to hash out implementation. For government contractors, the reality is that building DPI will still require significant IT work, just more standardized. Contractors who adapt can win contracts to build the new infrastructure.

• Political will and public perception: In today’s polarized environment, getting bipartisan support is tricky. Fortunately, DPI can be a bipartisan win if framed correctly.

For conservatives and fiscal hawks: emphasize the anti-fraud, waste-cutting angle. Stopping improper payments (recall that $236B figure!) and preventing identity theft aligns with the goal of efficient government. It’s essentially plugging leaky buckets, something everyone can get behind.

For liberals and tech-progressives: emphasize equity and empowerment. How digital infrastructure can help the unbanked access financial services, ensure eligible people aren’t left out of benefits, and give individuals control of their own data (a pro-consumer, anti-monopoly stance). Indeed, digital public goods are often framed as a way to ensure big tech doesn’t exclusively control our digital lives.

The key will be avoiding hot button mis-framings: this is not a surveillance program, not a national social credit system, etc. It’s an upgrade to basic government digital infrastructure. One strategy is to start with pilot programs and voluntary adoption to build trust. For example, the Act could fund a pilot in a few states to link a state’s digital driver’s license with federal Login.gov accounts, showing a working federated ID in action. Or pilot using FedNow for a chunk of tax refunds in one region. Early successes will create momentum and help refine the approach. Champions in the Congress will need to communicate that this is infrastructure in the truest sense: just as U.S. needed electrification and interstate highways, it now needs the digital equivalent to keep America competitive and secure.

By enacting a DPI Act, Congress can ensure that when Americans interact with their government or economy in the digital realm, it is as smooth and reliable as driving on the interstate or flipping on the light switch.

Originally published by Mitul Jhaveri on his Substack. Republished with due acknowledgment of the author and source.

Author

Mitul Jhaveri

Mitul Jhaveri is a Graduate Research Assistant at the Block Center for Technology & Society at Carnegie Mellon University, where he works at the intersection of artificial intelligence, energy, and public policy. His research focuses on how governments can collect better data and make more informed decisions on emerging technology issues.In addition, he is engaged as a Short-Term Consultant with the World Bank Group’s GovTech unit, contributing to digital transformation and data governance initiatives aimed at strengthening core government systems.He specializes in digital government reforms, leveraging data for policy decision-making, and enhancing public service delivery through technology.