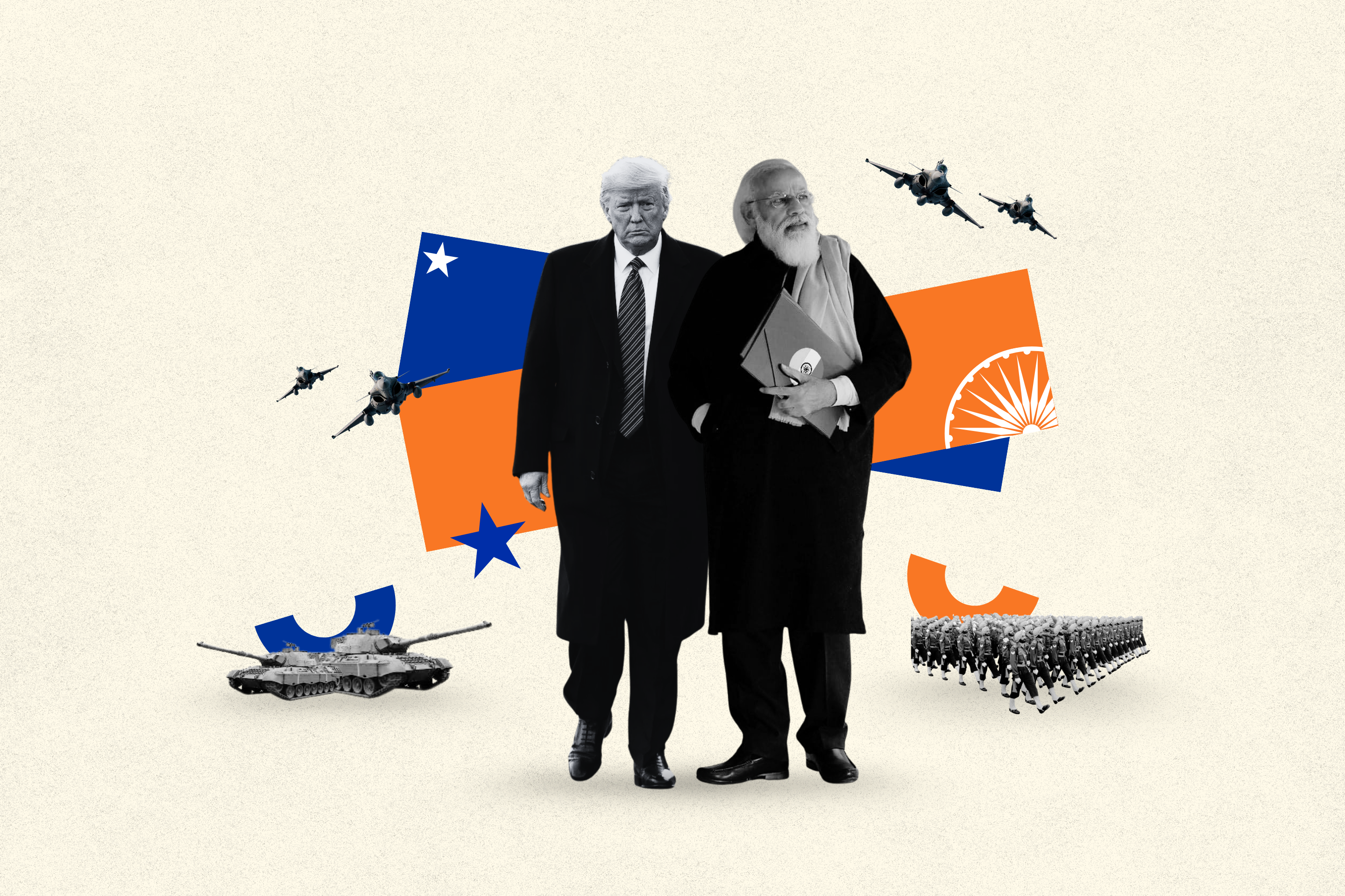

On Friday, 31 October 2025, the Governments of India and the United States formalized a significant strategic agreement known as the “Framework for the US‑India Major Defence partnership”. This Framework sets a ten‑year roadmap for defence collaboration between the two nations. The accord was signed by India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth on the margins of the 12th ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

This new Framework for the US‑India Major Defence Partnership institutionalises a long‑term strategic cooperation, unlike more limited previous agreements. The new framework encompasses a multi‑domain cooperation: Land, Sea, Air, Space, Cyber and Undersea, thereby strengthening strategic trust and enabling better alignment of defence policies and planning cycles. When viewed as a whole, this expansion across multiple domains emphasizes on the operational integration that signals the India‑US defence relationship is moving well beyond short‑term, and more of a transactional cooperation which will lead to a more stable, long‑term strategic partnership. It does not constitute a broad ideological alliance, but instead a pragmatic understanding formed in response to shared strategic concerns.

Rajnath Singh, Minister of Defence, wrote on X that India’s support for the rule of law and free navigation in the Indo‑Pacific is meant to safeguard regional interests, not oppose any nation. Last year, in February 2024, Hegseth and Singh reaffirmed their commitment to the US‑India Defence partnership, agreeing to advance operational cooperation, strengthen defence industrial and technological collaboration to support deterrence in the Indo‑Pacific.

But why focus so much on the Indo‑Pacific region?

Karl Haushofer’s early 20th‑century geopolitical writings remind us that the idea of “Indo‑Pacific” is not merely a contemporary strategic construct, but one with deeper historical roots. Haushofer conceptualized Indo‑Pacific as a single, unified geopolitical oceanic sphere, which he termed a “counterspace”, a strategic expanse capable of challenging the dominance of Western Maritime powers. In his view, powers such as Japan, China and India held the potential to achieve political self‑determination and form an anti‑colonial coalition, a grouping that could collectively resist Western European dominance. While the contemporary Indo‑Pacific narrative focuses on supply chains, maritime security, strategic competition, and the rules‑based order, its deeper lineage reveals a long‑standing recognition of the region as a critical geopolitical arena where major powers coalesce, compete, and redefine global governance norms.

Since the 1950s, the US has shaped the regional order through the San Francisco system, a “hub and spokes” network of alliances across the Asia‑Pacific that reinforced US strategic dominance and provided security guarantees to its partners. A major shift came in 2017, when the Trump administration officially adopted the term “Indo‑Pacific”, replacing “Asia‑Pacific” in US strategic discourse. This shift can also be a recognition in Washington that existing institutional tools are no longer sufficient to manage emerging challenges or the main influence in the region.

India’s focus on the Indo‑Pacific builds on long‑standing strategic thinking rather than representing a new shift. Ideas such as the Look East Policy and the “extended neighbourhood” had already encouraged India to view its interests as spanning from the Gulf of Hormuz to the Strait of Malacca and across West, Central, Southeast, and East Asia. K.M. Panikkar reinforced this view by describing the Indian and Pacific oceans as a continuous geopolitical space shaped by shared histories and key maritime choke points. Drawing the civilizational and geographic continuity, India presents its Indo‑Pacific vision as a natural evolution of its historical outlook. Today, India advances this vision through policies such as “Act East to Act Indo‑Pacific” and “Neighbourhood First”, which aim to cultivate deeper partnerships across a wide arc of countries.

Shared concerns

The signing of the recent defence pact between New Delhi and Washington is a historic step that comes at a complex moment. It coincides with persistent trade tensions between the two countries, yet both nations appear committed to ensuring that disagreements over tariffs don’t overshadow converging strategic interests. As Defence Minister Rajnath Singh wrote on X, the agreements are to “Usher in a New Era”, signaling that political differences in economic domains will not derail deeper military cooperation where mutual stakes are higher. This pact broadens the spectrum of exchanges between the two nations, spanning intelligence sharing, high technology cooperation and access to the defence market.

Beyond the institutional framework, India and the US share a fundamental concern: China’s increasingly assertive behaviour – along the Line of Actual Control, in the South China Sea and across the Indo‑Pacific, where China is challenging US hegemony through its military and economic projects like Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and blue water navy to establish itself as a leading power. American isolationisms enabled China to expand its regional influence and consolidate its position as a significant military power. This shift is reflected in China’s possession of the world’s largest navy in terms of the number of vessels and its growing dominance across Asia.

The Washington administration’s Indo‑Pacific strategy appropriately recognizes the necessity of a stronger response to Beijing’s destabilising actions and its coercive tactics toward regional allies. Such actions have not only compromised the US interests but have also eroded the sovereignty of Indo‑Pacific partners. In order to counter China’s expanding influence in the region, the US must deepen its partnership with a state recognized globally not only for its economic weight but also for its adherence to a rule‑based order and international norms.

As India is strategically positioned at the heart of the Indo‑Pacific, New Delhi has emerged as an indispensable partner in efforts to balance China’s rise. India’s strength lies in its geostrategic location, and growing capabilities make it a particularly valuable actor for strategic convergence with Washington. Nevertheless, India’s engagement in the Indo‑Pacific is likely to differ from that of the US, while Washington is expected to pursue a proactive, security‑oriented approach, New Delhi may adopt a more restrained and observatory stance, shaped by its own strategic autonomy and regional priorities.

Rajnath Singh has strongly emphasized in his X post that India is committed to the rule of law, freedom of navigation and overflight in the Indo‑Pacific. It further stressed that New Delhi does not act against any country, but the challenge posed by China cannot be overlooked. It is very important to recognize that China’s increasing belligerence has, in fact, compelled India to accelerate the pace and significance of the Quad. And, even though India and its partners seek to strengthen their bilateral and multilateral cooperation within the framework of the Indo‑Pacific and the Quad, the implications of China’s rise remain an unavoidable strategic consideration.

China’s military modernization, naval expansion, and coercive activities across maritime and land domains have pushed India to seek stronger partnerships. New Delhi’s limited ability to counter China’s rising power projection independently makes US cooperation valuable for:

- • Balancing China’s military weight in the Indian Ocean Region(IOR).

- • Providing regional states, an alternative to reliance on China’s economic networks.

In this context, the India‑US defence pact stands out as the most concrete and consequential area of cooperation between the two countries, ensuring that Beijing’s rise will not go uncontested. While the QUAD remains an essential framework, the India‑US defence pact is not an alliance; rather, it provides its states with a platform to manage differences and deepen cooperation across a range of sectors. Ultimately, strategic partnerships can evolve, but geographic realities cannot be altered.

The coming decade will test India’s ability to engage with the US to strengthen its deterrence posture while preserving strategic autonomy. As cooperation deepens, the India‑US defence relationship can serve as a stabilising anchor in an increasingly contested Indo‑Pacific region.