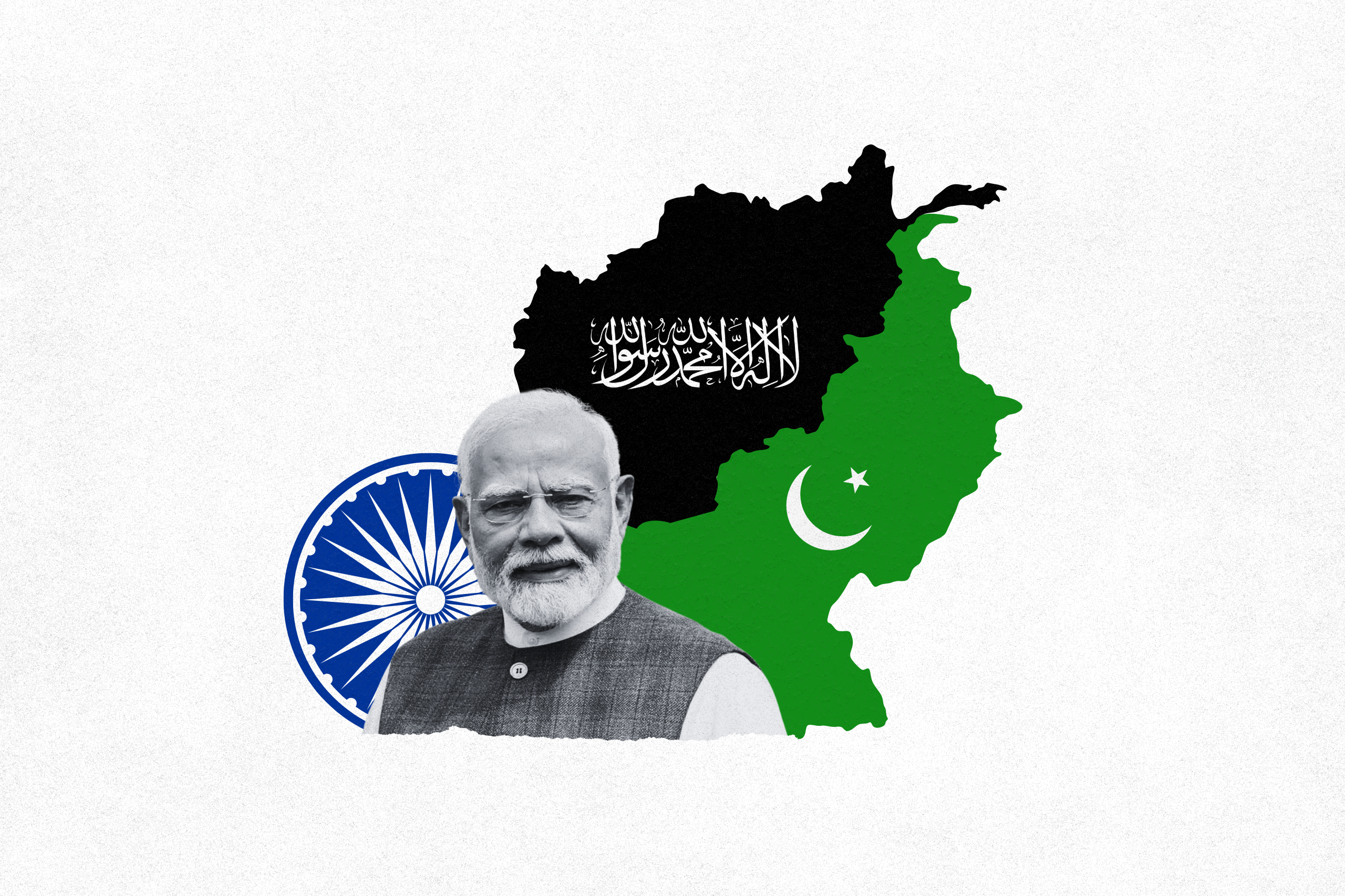

Two important leaders of Afghanistan just visited India back‑to‑back, ending the long‑standing restrained foreign relations between India and Afghanistan. The visits mark a significant shift in India’s regional posture, as Afghanistan has long been a playground of Pakistani experiments and proxy wars. This visit not only signals Indian readiness to get into the muddy geopolitics of Afghanistan but also Indian readiness to deal directly with the extremist group and counter Pakistan’s superiority in Afghan politics.

India‑Pakistan Rivalry and Afghanistan

To understand why these visits matter, it is necessary to step back and examine the political and historical forces that shaped Afghanistan’s regional role. At the centre of this story lies the enduring rivalry between India and Pakistan. It would not be wrong to say that India and Pakistan have a long, celebrated rivalry. The roots of this rivalry stem from partition and span decades of political, territorial and emotional contestation. Terrorism is a big part of this rivalry and has been a cause for many conflicts between the two neighbours. Regional consequences have further coloured this rivalry, and Afghanistan is a key point of contention. Pakistan has always used Afghanistan to maintain its idea of strategic depth, implying Afghanistan as Pakistan’s buffer zone with India. To maintain this buffer zone, Pakistan aimed for complete control of Afghanistan. This ulterior motive of Pakistan was never subtle but direct and brutal in action. Pakistan maintained a clear hand in many of Afghanistan’s conflicts and crises.

Afghanistan’s Tumultuous Past

Afghanistan’s internal political history is central to understanding how it became so deeply enmeshed in regional power struggles. Afghanistan is a land with a long history of foreign conquests, characterised by warring factions competing for control and navigating its difficult and often unforgiving terrain. As a gateway between Asia and Europe, the land carries immense geopolitical significance.

During the 1950s, Afghanistan had a Soviet‑friendly government under King Zahir Shah and Mohammed Daoud Khan as Prime Minister. In 1973, the monarchy in Afghanistan was abolished following a military coup that brought Daoud Shah to power. The Republic of Afghanistan was established, and the Soviets exerted significant influence in the early years of the new republic. This influence waned, and Daoud Shah initiated a non‑aligned foreign policy, striking a balance among other regional powers, including those in the Gulf and India.

This period was also tumultuous for Afghanistan‑Pakistan relations since Daoud started proxy warring against Pakistan using the Pashtunistan project, which Pakistan was already struggling with. In retaliation, Pakistan under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto started funding and abetting Afghan rebels. This strategy ultimately backfired for Daoud Khan, leading to a shift in relations with Pakistan that was detrimental to Soviet interests. It is also during this period that a new constitution was established, granting women more rights. This constitutional reform marked a turning point for Afghan women, who had long been constrained to the domestic sphere.

By the late 1970s, this fragile political balance collapsed entirely. In 1978, the Afghan communist party assassinated Khan and took control of the government, declaring the creation of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. This period saw the rise of internal strife in the communist party, where brutal suppression and executions became an everyday reality, alongside the growing rebellion of Islamist groups along the borders.

The crisis soon escalated beyond Afghanistan’s borders. On the pretext of international aid, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 against the Islamic rebels, covertly funded by the Americans. Under General Zia‑ul‑Haq, Pakistan provided support to the Mujahideen, with heavy financing from the US and Saudi Arabia. Millions of Afghan refugees fled to Pakistan at one point—more than three million, the largest refugee population in the world. In 1992, the Soviet‑backed Afghan government fell and gave way to Islamist factions taking power. These Islamist factions of rebels would later consolidate into what the world now knows as the Taliban. The Taliban, supported and influenced by Pakistan, came into power during this period.

The attacks of 9/11 marked another decisive rupture for Afghanistan, and Pakistan actively assisted the United States in ousting the Taliban. This period saw Pakistan’s double‑edged policy of covert support to Taliban leaders while publicly aligning itself with US‑led counterterrorism efforts. From 9/11 until the return of the Taliban, Pakistan both overtly and covertly supported Taliban leaders, enabling them to find sanctuary and sustain recruitment efforts.

Taliban‑Pakistan Tensions Today

In recent years, this arrangement has begun to unravel. However, the current events of the deteriorated relationship between Pakistan and the Taliban reveal the long‑term dangers of state‑sponsored militancy. Driven by its aspiration to see an Islamist government in Afghanistan, Pakistan failed to fully anticipate the long‑term costs of financing a terrorist ideology. The current relationship between the Afghan Taliban and Pakistan is not just estranged but dangerously escalated, with cross‑border strikes becoming increasingly frequent. Since these strikes, the Pakistan–Afghanistan border has been closed, affecting trade and civilian movement.

The consequences have been immediate and economic. Last month, Pakistan closed its border with Afghanistan for trade and civilian movement following deadly military clashes. Kabul is now seeking to expand trade relations with India and has urged New Delhi to establish cargo hubs on Afghan soil. Long dependent on Pakistan for trade, Afghanistan has increasingly looked to diversify its trade routes in the wake of border clashes and repeated closures.

India‑Taliban Engagement: A New Chapter

This opening created space for India to step in. Against this backdrop, India launched a strong initiative to establish direct trade ties with the Taliban leadership, a move consistent with its enduring strategic interest in Afghanistan. This shift created an opportunity for Afghanistan to reduce reliance on Pakistan and for India to gain direct economic access, which both countries recognised by initiating their first meeting in October 2025.

Diplomacy soon followed trade considerations. The Taliban’s Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, undertook a six‑day visit to India, holding talks with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishanker in October 2025. This development marked a departure from India’s traditional diplomatic restraint, as New Delhi engaged with an individual subject to United Nations sanctions. The significance of the meeting was heightened by the fact that it was India’s first engagement with a high‑ranking Taliban official.

The discussions culminated in a joint statement emphasising trade, connectivity and cooperation, with Indian companies invited to bid for Afghan mining licences, the launch of the India–Afghanistan air freight corridor, and collaboration on hydroelectric projects and humanitarian issues. Notably, the talks avoided contentious issues and made no reference to India’s 2024 UNSC statement calling for counterterrorism, inclusive governance and the protection of women, children and minorities in Afghanistan.

This engagement was followed on 19 November by a five‑day visit to India by the Taliban administration’s Minister of Industry and Commerce, Alhaj Nooruddin Azizi. The most consequential outcome of both meetings was the air freight corridor linking Delhi, Mumbai and Amritsar with Kabul and Kandahar, aimed at strengthening direct trade and connectivity. Bilateral trade would primarily involve Indian exports of pharmaceuticals, textiles, machinery, sugar, tea and rice, in exchange for Afghan agricultural produce, including fresh and dried fruits, and select minerals.

Conclusion

Taken together, these developments signal a broader realignment in the region. The Afghan visit represents a significant milestone in India’s regional diplomacy as it underscores the gradual erosion of Pakistan’s long‑standing dominance over Afghanistan. For decades, Pakistan constrained India’s access not only to Afghanistan but also to regions such as Iran and Central Asia. India’s engagement with the Taliban opens new avenues for regional connectivity, notably through initiatives like the Chabahar Port, allowing New Delhi to bypass enduring geographical and political constraints imposed by both Pakistan and China.